Scrapyard workers recount fiery impact of UPS plane crash in Louisville, Kentucky

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (AP) — Supervisor Adam Bowman was loading metal onto a truck at a scrapyard just south of the Louisville, Kentucky, airport when he heard what he first thought was a transformer explosion and quickly realized was more horrific.

“I turned around and I see over the fence just a huge cloud of black smoke and just a fireball that was indescribable,” Bowman said. “I’m thinking this is a plane coming down.”

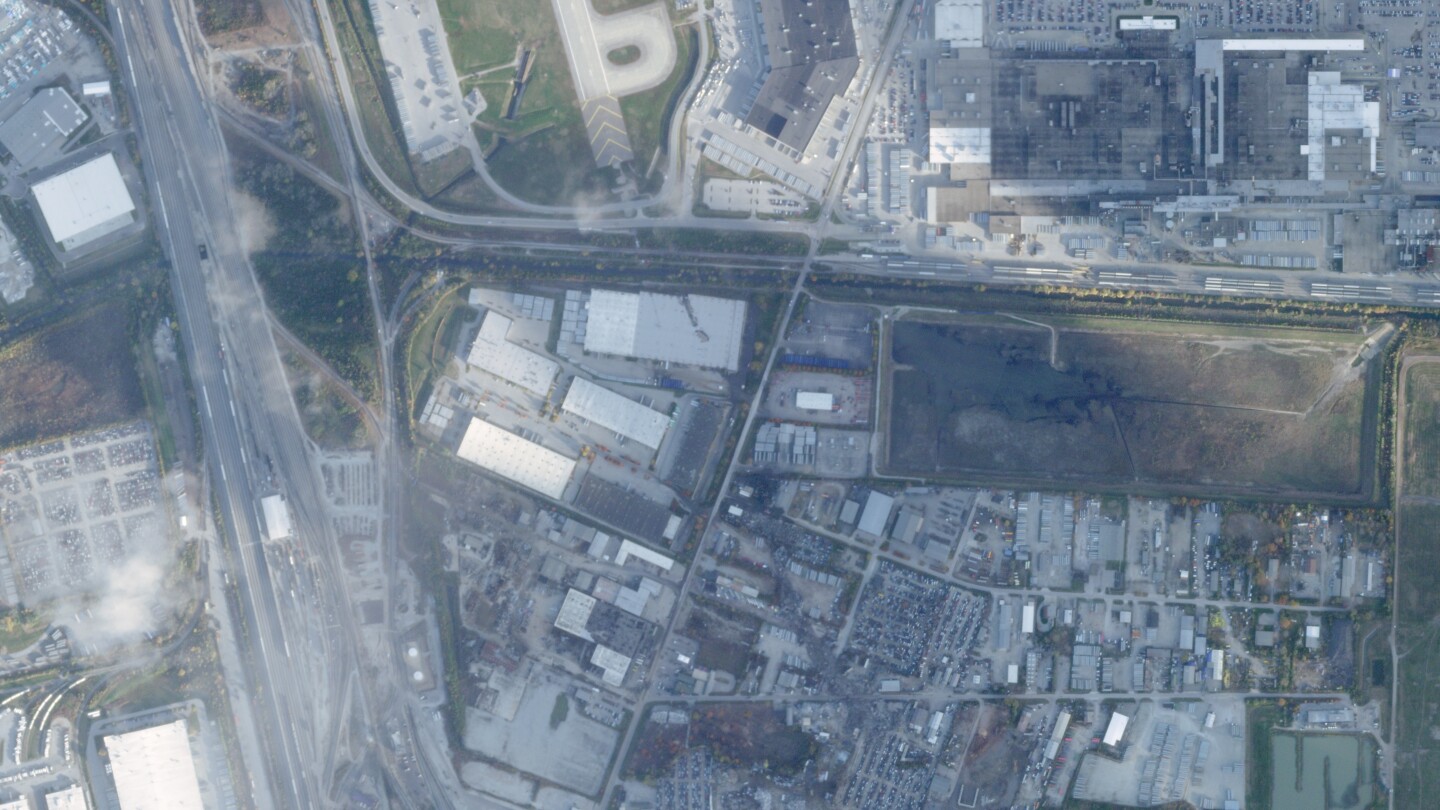

And it was: A UPS cargo plane had crashed as it tried to take off, sparking a devastating ripple effect that hit Grade A Auto Parts & Recycling and caused blasts at nearby Kentucky Petroleum Recycling.

Bowman said he initially didn’t know whether to run or take cover but chose the latter, diving between giant aluminum bales and curling up as tight as he could as explosions and fires erupted without warning.

The horrors were just starting for him, his co-workers and customers who had gone to turn scrap metal into cash at Grade A, a sprawling 30-acre facility.

Back on his feet and scrambling for survival, Bowman heard someone cry for help. Through black smoke he spotted a man unable to flee, so badly burned his clothes were scorched off.

“I told him, ‘Get on my back. We’re going to get up front. We’re going to get you help,’” Bowman told The Associated Press.

Chaos at the scrapyard

On the other side of the scrapyard, Joey Garber had been reviewing emails in his office at Grade A when the power flickered off, the building shook and he heard a series of explosions.

The plane had crashed about 5:15 p.m. on Nov. 4, after its left wing caught fire and an engine fell off as it was departing for Honolulu from UPS Worldport, the company’s global aviation hub in Louisville. The National Transportation Safety Board is investigating the crash, which was captured in dramatic video.

Garber said he ran out the door and saw the flames and black smoke. After that, it was chaos as people struggled to find a path to safety.

Garber, 30, chief operating officer and a son of the Grade A owner, said he saw two employees holding onto each other, somehow crawling out of a fire. He spotted another coworker and shouted for her to run toward him. Then another explosion rocked the scrapyard.

“The heat that came off that explosion was so hot that we all stopped moving,” he told the AP. “I remember looking at my boots thinking to myself: ‘You’ve got to move your feet again. You can’t stay here. You’ve got to go.’ ”

Burned man rescued

Outside, once he thought the risk of flying debris had diminished, Bowman rose to a hellish scene.

“Everything was on fire,” he said.

He said he ran toward a building but reversed course when another explosion erupted nearby. He called his wife and parents to let them know he was OK. When his dad asked what had happened, Bowman recalls replying: “I’m pretty sure a plane went down and I think everybody’s gone.”

Soon after, he heard the plea for help from the burned man.

“All I can think is this guy’s got a strength and will that he’s got to have some people he loves he’s trying to get to,” Bowman said.

Bowman, 44, said he carried the man piggyback, trying to reassure him, and contacted a coworker who steered through the chaos in his pickup truck. They loaded the man into the truck and drove until they found emergency workers for help.

Bowman asked for the man’s name and learned he was Matthew Sweets, 37.

Sweets, an electrician and father of two, would die days later, one of the 14 people killed in the crash.

A question of rebuilding

More than a week later, Garber marvels at the miracles for those who were able to make their way to safety.

Bowman becomes choked with emotion while recounting his actions but downplays his act of selflessness. He wonders what will become of the now-charred scrapyard where he spent 15 years building a career.

Sean Garber, owner and CEO of Grade A, said the physical heart of the business was destroyed, and he doesn’t know if he will rebuild on the site.

“I’d like to say ‘yes,’ but I just simply don’t know,” he said Thursday.

He was on a business trip in Florida when he heard his recycling business — which averaged 200 to 300 customers daily — had been wiped out.

His chief financial officer called in a panic, saying the power was out and that it felt like an earthquake hit. Then she alerted him the scrap metal office had blown up. When she turned the camera to FaceTime, Garber heard explosions and saw a fiery mushroom cloud.

It would leave him mourning the deaths of three employees — John Loucks, 52; Megan Washburn, 35; and Trinadette “Trina” Chavez, 37 — and the customers who died, including a man and his young granddaughter. Three pilots also were killed.

Sean Garber said he has shared a roller coaster of emotions with his employees since the crash — the initial shock that turned to grief over their lost co-workers. Now there is anger that the tragedy happened, he said.

Grade A workers were tightknit, spending as much time among each other as they did their own families, Bowman said. Then in a flash, three of them were gone. The survivors wonder how such a horror ever happened.

“I told the whole team that everyone that walked away, we have an obligation to our friends and our co-workers who didn’t to live our lives to the fullest,” Joey Garber said.